During a large part of James Monroe’s time as president of the United States, he faced growing conflicts between Native American populations and white settlers seeking to colonize their lands. When President Monroe first took office, his position toward the Native American populations was that provisions should be made to ensure that they could have access to improve their education and that they would then be able to integrate into civilized life. This was a direct departure from the previous president’s policy towards the Native populations, where they mainly focused on obtaining tribal land and conquering the people. Monroe addressed his attitudes concerning the rising conflict between Native Americans and white settlers in his annual message to congress on November 16, 1818:

“Experience has clearly demonstrated that independent savage communities cannot long exist within the limits of a civilized population . . . To civilize them, and even to prevent their extinction, it seems to be indispensable that their independence as communities should cease, and that the control of the United States over them should be complete and undisputed. The hunter state will then be more easily abandoned, and recourse will be had to the acquisition and culture of land and to other pursuits tending to dissolve the ties which connect them together as a savage community and to give a new character to every individual. I present this subject to the consideration of Congress on the presumption that it may be found expedient and practicable to adopt some benevolent provisions, having these objects in view, relative to the tribes within our settlements.”

On March 3, 1819, The United States Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act (also known as the Indian Civilization Act or Civilization Act). This act was initially passed to encourage various societies to provide education for the Native American populations. President Monroe believed that if the Native American population were to have access to education, it would prepare them for successful assimilation into white society. Many of the societies that were involved with the assimilation efforts were often Christian missionaries. Within eleven years of the act being passed, fifty-two schools opened. They were explicitly designed to force Native people to renounce their cultural ties in favor of adopting those aligned with white society. The federal government saw the Civilization Act as a means for the Native American populations to assimilate without conflict between the United States and the tribes.

Passage of this act set a precedent leading to numerous Native American lives being lost. One of the many laws that followed the Civilization Act was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, passed during the presidential administration of Andrew Jackson This act is one of the most well-known and detrimental policies to impact Native Americans during this time. The Indian Removal Act allowed the President to grant lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for Native lands within existing state borders. This legislation primarily affected the Cherokee tribe. While some tribes left their land peacefully, fearing conflict with the American military, many decided to stay and fight to keep their lands. Those who decided to leave did not face a kinder fate, though. The Native Americans who ceded their lands to the United States were forced to relocate elsewhere and were driven forcibly to their new lands along the Trail of Tears. During their year-long march, nearly four thousand Cherokees died.

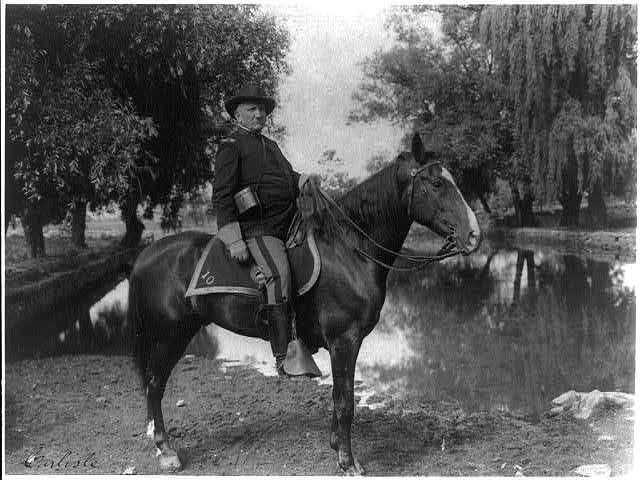

Another impact of the Civilization Act was the eventual formation of the federally mandated Indian Boarding Schools. The most prolific of these schools was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879 by U.S. Army Lieutenant (later General) Richard Henry Pratt. A veteran of several campaigns during the Indian Wars on the Great Plains, Pratt began a program to assimilate Native Americans into white culture in 1875 while supervising prisoners at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida.

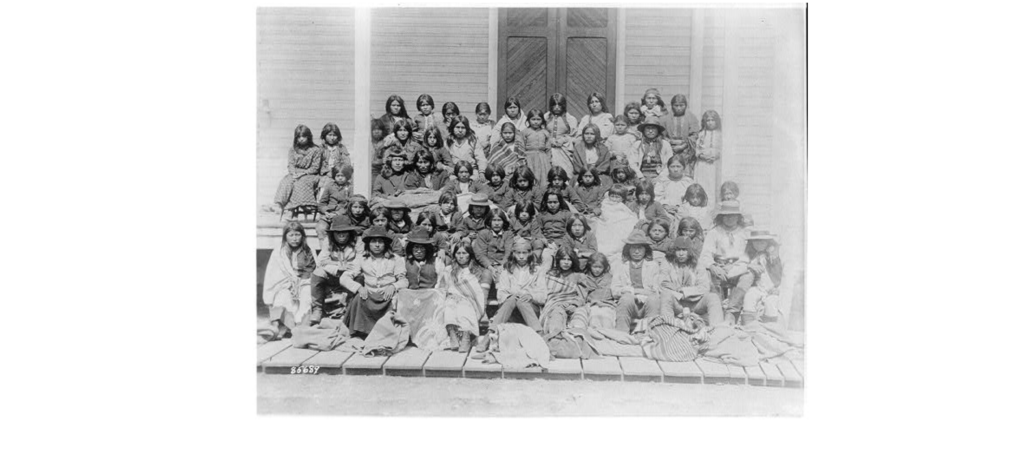

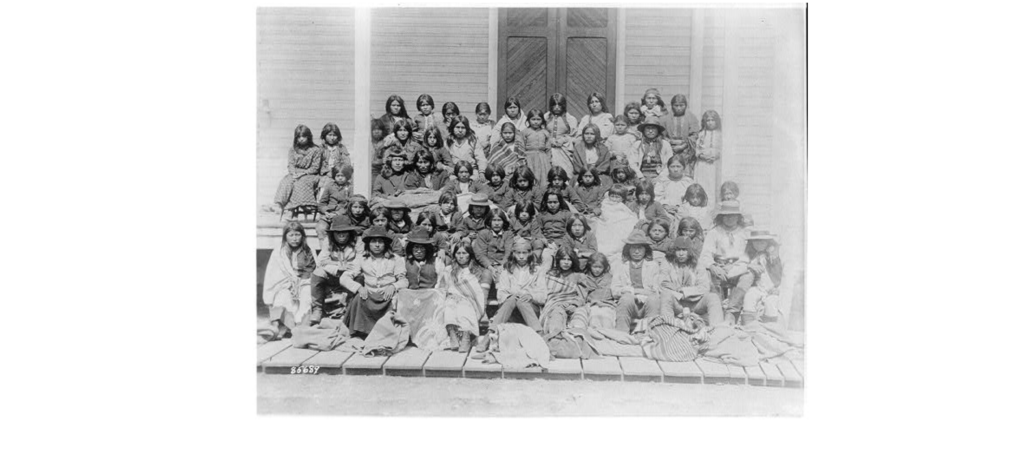

Pratt described his assimilation methods: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” The boarding schools during the late nineteenth century departed from the schools formed under Monroe’s presidency in one major way: The early schools focused more on religious conversion, whereas these focused on complete reeducation and assimilation achieved by removing any reminders of Native culture the children who were forced to attend would have during their time at the schools. When they arrived, the children had their pictures taken before they were stripped of their tribal clothes and the boys had their hair shorn. For many tribes, hair holds extreme significance and often reflects a source of strength and power. In addition to this, children were not allowed to carry medicine bags, jewelry, or ceremonial items. The boys were forced into military uniforms, and the girls were put in long skirts and corsets, popular fashion for white women during the Victorian era. After the children had all physical demarcations of their tribal affiliation removed, they were forced to have their pictures taken. These pictures essentially acted as proof that Native Americans were able to look American and were, therefore, able to integrate into American society if given the proper means of education.

After the children were stripped of the physical identifiers of their tribal affiliation and way of life, they were also made to choose a new Anglican name. In many Native American cultures, names hold profound significance. By stripping children of their tribal-specific names, Pratt effectively removed everything that the children recognized as being their own, including their identity.

Children were denied communication with their families while attending school, including during the summer months. When school was not in session, the children were not permitted to return home; they instead were sent to live with white families. This was likely to ensure that the children remained isolated from their family and culture while maintaining a relationship with American culture. While at school, half of the day was spent studying English, math, geography, and music. The other half was spent in vocational training, where boys learned industrial skills and girls learned how to run a house properly. Under the rule of Pratt, these children were deemed assimilated and had the opportunity to leave their tribal life and integrate into American society.

While it is easy to think that James Monroe’s advocacy of the Civilization Fund Act of 1819 was an isolated incident and had no lasting impact, this is simply not the case. The codifying of assimilation practices during his administration established an important precedent for the subsequent degradation of Native Culture and forcible removal from traditional tribal lands. President Andrew Jackson and Richard Henry Pratt used this to their advantage in their efforts to maintain control over the Native population. The boarding schools that began with, and evolved from, the Civilization Act have recently come to light as an important but overlooked aspect of the assimilation process. The schools that were formed as a result of the Act robbed generations of Native American children of their cultural identity and caused the deaths of thousands of them- another Trail of Tears that lasted over 150 years.